Last year around the month of November, two of our collaborators fulfilled their dreams: to get to know the people, the harvest, the processing and the terroirs of Ethiopian coffees up close. Claudia Sans Witty and Cássia Martinez de Carvalho spent two weeks traveling the roads of the prestigious South and West regions of the country together with a team of exporters, importers, tasters and roasters of the highest caliber.

With their experiences we were able to see with better focus the care and difficulties in the cultivation of coffee trees, the care in each stage of the processing and to better understand how their new export system works due to profound political changes made that year by the Ethiopian Commodity Exchange (ECX).

They understood firsthand how rooted coffee has been in Ethiopian culture for centuries and centuries, experiencing coffee ceremonies, tasting, getting to know the rural landscape, its cuisine and falling in love with the cradle of Arabica coffee and its people.

Claudia Sans, taster and owner of Cafés el Magnífico and our collaborator and taster Cássia Martinez tell us about their experience:

COFFEE ROUTE THROUGH ETHIOPIA ONE DAY AT A TIME

November 05, 2017

ADDIS ABEBA “Nueva Flor”

With the possibility of acclimatizing to the country one day before starting the expedition to the south of Ethiopia, we spent the first day getting to know the Abyssinian capital. As soon as we stepped on the street and found THE highest ranking Orthodox Cathedral in Ethiopia we saw how small informal huts fill the spaces of the city offering among various products and services; coffee.

With a very warm smile, we were invited to approach each of these street coffee kiosks. We could not resist and we got stuck in the Dinkst and Amabit kiosk. In Ethiopia, the preparation of coffee is the sole preserve of women. Amabit roasts it (in a frying pan) and Dinkst grinds it and prepares it in the ceramic jebena.

Everywhere the coffee is served either with a sprig of Tena Adam herb or with a smoking pot with incense. Both of very aromatic character and very particular of the tradition of the coffee service in Ethiopia.

Known by the common local name tena’adam, Ruta chalepenesis is a shrubby plant grown in the highlands of Ethiopia. Descriptive of the plant’s smell and taste, “Ruta” is an old Latin name for rue, literally meaning bitterness or unpleasantness. Yes, this is the smell and taste of this curious detail that decorates coffee cups.

Another curiosity discovered in Ethiopia is that they have their own calendar. It is a solar calendar which in turn derives from the Egyptian calendar and starts the year on September 1 of the Julian calendar. A 7 – 8 year gap between the Gregorian (the one we use in Europe and most of the world) and Ethiopian calendars is the result of an alternative calculation to determine the date of the Annunciation. So when we were there (in 2017) for them it was still 2010.

As if that wasn’t confusing enough, many Ethiopians count the cycle of hours from sunrise to sunset. Being so close to the equator, in Ethiopia the day and night hours barely vary and they start counting the day from 6:00 am. So, if you need to know the date and time of an important appointment it is best to double check this information before scheduling.

Let’s go back to coffee…

A must-see in Addis is the Galani coffee shop!

From the same owners of Moplaco (Yannis and Heleanna Georgalis) and located next to their warehouse on the outskirts of the capital. Galani is a large space full of beauty where they not only serve the best coffee in town, but also offer trainings, sell high quality coffee machines and supplies, have amazing food (best peanut butter ice cream of your life) and maintain a cultural space for Ethiopian art, crafts and events.

We have been asked not to take pictures inside the place; I can imagine how unpleasant it can be for people dazzled when they enter the place to shoot crazy pictures. However, for the more curious, on the internet you can see what Galani looks like inside.

Galani took its name from the Gelan River, which runs through the Bale Mountains all the way to Arba Minch, crossing through many of the coffee-growing areas in the south of the country. Coffee beans in most of those regions are transported on donkey herds, so the logo and the name came together to form its identity.

Heleanna’s father, Yannis, with whom our boss Salvador Sans toured Harrar in 1996, was a collector of donkeys, “the noblest and hardest working animal,” he said.

November 06, 2017

ROAD TO THE SOUTH

Heading south, still on easy roads, we drank rich strawberry milkshakes grown on the farm where they were served to us. On the fork between Oromia and the Southern Nations (Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region, or SNNPR), we stopped for lunch among monkeys on the shores of Lake Awasa. We pass through the famous village of Shashamane, a territory ceded to the Rastafarians 55 years ago by the then King Haile Selassie, and continue to Yirgacheffe.

With the roads in a precarious state, even in 4×4 the trip becomes very long and tiring. We arrive at the hotel late at night, and without dinner, our guide tells us that we have 15 minutes to return to the car with boots and flashlights to visit the first washing station of the trip. This was no joke.

At harvest time the work does not stop; if cherries have been harvested in the field until late, they must be pulped and put in fermentation tanks immediately to avoid any fermentation of the pulp between harvesting and washing.

KONGA SEDIE WASHING STATION

So our first washing station was Konga Sedie in the town of Konga (name of the nearest village to the benefit). It was 22h on the European clock!

Konga Sedie harvests 1,000kg of cherries per day and processes one batch per day during the harvest season. When the cherries arrive at the mill, they are weighed and dumped into a huge concrete funnel that gravity feeds them with the help of water from the river near the pulper.

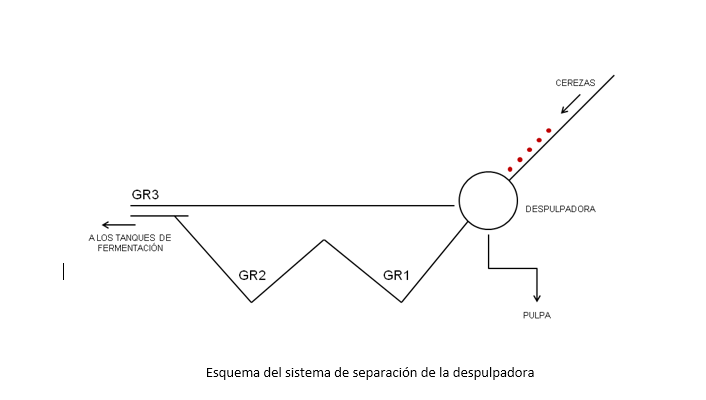

The pulping machine itself separates the seeds into three categories (grades 1, 2 and 3) on the one hand and on the other discards the skin (or husk) of the cherries that will be used as fertilizer later.

Freshly pulped grade 1 coffee shines due to the presence of mucilage still adhering to its surface.

Grade 1 seeds are the largest seeds and remain in the fermentation tanks for 2 days; grades 2 (medium size) and 3 (small) are washed the following day.

In the fermentation tanks they use water from water tables that is pumped from a 72m deep well on the mill itself as it is much cleaner than the water from the nearby river.

November 07, 2017

The next morning, before moving on to our next wash station we were able to see in daylight what the village of Yirgacheffe looked like, this name that resonates so much with us when referring to the cafes of southern Ethiopia.

It turns out to be a very, very simple town, where many people have coffees from their gardens exposed on tarpaulins for drying on the side of the road. Between goats and mud the coffee is dried for family consumption or used as barter in the local market.

I don’t know if for you the reader the Ethiopian origin coffee denominations are also confusing, but to us it always seemed very chaotic to understand what exactly is Yirgacheffe, Sidama, Oromia… what is region, what is locality, which micro region is within which etc.

So we could not be in the most appropriate place and with the most appropriate people to clarify these concepts for us. Between our team of exporters and producers of Ethiopian coffees and veteran European importers (not without a long exchange of uncertainties and information between them) I have been able to elaborate this simplified diagram that illustrates the territorial subdivisions of the coffee growing areas of Ethiopia. It is worth noting that sometimes the name of the locality coincides with that of its district (a bit like what happens with Barcelona city and Barcelona province) and that terms such as Yirgacheffe are also being used to denominate a cup profile although cultivated outside the limitations of Yirgacheffe…

In short, many doubts have been clarified but others remain, both for us and for them since territorial boundaries are almost always political demarcations and those demarcations are still very new and/or fluctuating in present-day Ethiopia. Especially the regions, or what we could call the major land enclosures of the country, have very irregular or scattered shapes in different ‘spots’ scattered on the Abyssinian map. Let’s say that organization and practicality is not the strongest thing in this country.

WORKA CHELCHELE WASHING STATION

Arriving in the area of Gedeo we visit the washing station of Worka Chelchele. So by the logic we just learned we are in:

REGIÓN: Sur (SNNPR)

ZONE: Gedeo

DISTRICT: Gedeb

KEBELE: Chelchele

WOREDA: Mokonissa

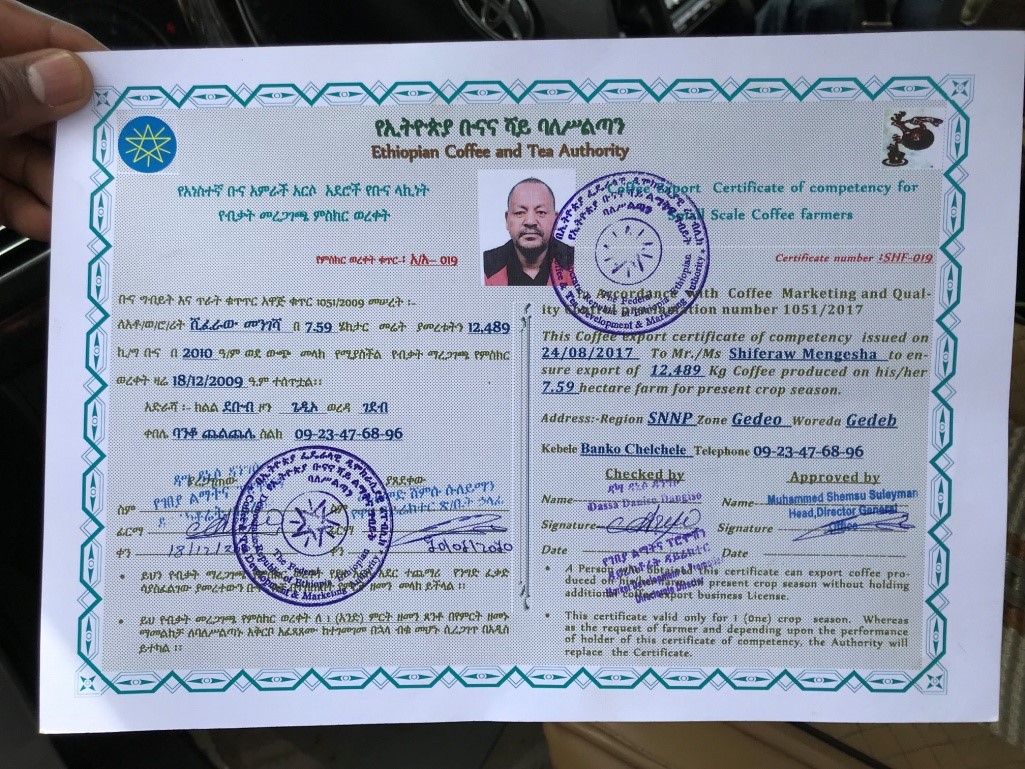

This washing station receives coffees from small coffee farmers such as Shiferaw Mengesha who has a 7 ha plantation, an extension of land known in Ethiopia as a ‘coffee garden’. Shiferaw together with Adugna have one of the first coffee export licenses independently of the ECX (Ethiopian Commodity Exchange). They are now collaborating with 15 other small coffee farmers helping them to get their own export license, giving support in the quality of processing and conservation of parchment coffee and supporting them in agronomic practices so that the quality and price of their coffees go up. In this way, these 15 coffee growers can share the costs of certification and export their production directly to importers around the world.

These 15 farmers help each other by rotating their work in groups of 5 to weed and keep the 7-year-old coffee trees well fertilized. They grow the Kurume and Walesho varietals and two other high-yielding varieties brought from the Jimma Research Center, named 741110 and 741112 for the time being.

Adugna, who used to work for the government inspecting the quality of export coffees, is now the agronomist in charge of a nursery with 170,000 Kurume and Walecho seedlings. First they plant the seeds in the soil and after 7 months they transfer the cuttings to plastic bags (photo) and only after 1 year they can sell them or distribute them to the 15 members of the washing station. With these coffee plants they have a productivity of 1,600kg of green coffee/ha and are receiving governmental awards for the quality of their coffees and therefore have a much easier time obtaining export licenses.

ON CHANGES IN THE EXPORT MARKET

The Ethiopian Commodity Exchange (ECX – Ethiopian Stock Exchange) was established by the Ethiopian government in 2008 with the intention of democratizing market access for farmers growing coffee, beans, maize and wheat among other crops. As farmers in Ethiopia tend to own very small plots of land (less than 1Ha) and are largely subsistence farmers – growing what they need for domestic use and selling the surplus for cash – it was decided that standardization would be the most egalitarian way to improve health and economic stability in the agricultural sector.

The ECX strove to eliminate sales barriers by offering farmers an open, public and reliable market to sell their products to for a fixed and relatively stable price. In its early days, ECX rules dictated that any coffee not produced by a private farm or cooperative society had to be sold through the Exchange, but this system removed the “specialty” label from coffee and turned it into a commodity, leaving all traceability aside, minus the basic information about region, type of mill and grade.

After much lobbying by the specialty coffee industry and several rounds of intense negotiations, a subsequent iteration established that washing station information would also be available, although tracing them back to their individual producers remained impossible.

In March 2017, the ECX moved to allow direct sales of coffee by washing stations, which will not only allow for greater traceability, but also allow for repeat purchases and relationship building along the chain. Thereafter, beneficiation owners in possession of a valid export license can sell their coffees directly on the international market, on the condition that they have a registered contract with the National Bank of Ethiopia within three days of their arrival at ECX warehouses. If the coffee is not sold after these three days, it will be sold on the existing ECX platform, but with its traceability intact.

It remains to be seen what the impact of these changes will be for Ethiopia, but the industry seems optimistic. It has surely been a revolutionary change for many producers in the country.

WORKA SAKARO WASHING STATION

Ato Mijane (Mr. Mijane), its owner, founded it in 2012 and Daniel Mijane, his son, has the sole objective of creating all the right conditions to produce the best that Yirgacheffe has to offer. They follow a strict quality protocol that is not high-tech, but still very effective.

REGION: Sur (SNNPR)

ZONE: Gedeo

DISTRICT: Gedeb

KEBELE: Sakaro

WOREDA: Worka

Worka Sakaro is another station that collects coffees from small producers, with a production of around 1 – 2ha. These small coffee growers are located in the Worka valley, most of them on the slopes of Mount Rudu (over 2000 meters above sea level). They have a close relationship with their producer partners whom they support with training and finance; another key strategy for accessing the best cherries.

Excessive rains in 2017 have delayed the ripening of the cherries and we have not been able to see the beneficiation process at Worka Sakaro. However, here the coffee is fermented for 24 – 48 hours and dried on African beds for approximately 7 – 10 days, depending on weather conditions.

We open a parenthesis to explain about the 4 categories of size and type of coffee plantations in Ethiopia. The first three production systems are traditional, where predominantly smallholder farmers are responsible for production management and the fourth is a modern production system.

The percentage indicates their contribution to national production.

Basically they are summarized, from smallest to largest::

-

-

- Garden (about 1ha) 5 – 10%: local varieties are harvested along with other family subsistence products that they grow in their private gardens near their homes.

- Foresta 45%: is harvested from wild plants in practically intact forest plots.

- Semi-foresta 35%: is harvested from semi-wild plants in forest fragments where farmers ‘thin’ the upper canopy and annually carve out part of the understory. This method of cultivation is a driver for the preservation of indigenous forest cover.

- Comercial 15%:is harvested from improved varieties in large monoculture plantations. Production is mainly interested in maximizing coffee yields.

-

Although the cherries were not yet at “candy point”, we were able to visit some of the farms that deliver their coffees to Worka Sakaro and, among them, we visited the 37ha farm of Edemi Gelgelu and his wife Elfinesh.

Back on the road and after eating tibs (spicy minced lamb) with kocho, we paused for coffee.

Kocho, also spelled ‘Qocho’, is a bread made from fermented starch extracted from the trunk of the Enset, which is a false banana tree.

It is very common in Ethiopia especially in the mountainous regions because at the altitudes where we were (above 2,000 meters above sea level) it is very difficult to harvest fruits and vegetables and Kocho is very rich in potassium, calcium, iron and vitamin A ensuring food security for 15 million people in the southwest of the country.

A very curious custom about coffee service in Ethiopia is that they always serve it in mini cups without handles (like the gyokuro tea cups in Japan), but what is really striking is that they always serve the liquid up to the edge of the cup or already spilled on the saucer that holds it (as they do with sake, again referring to Japan).

After being served this way so many times I realized it was a habit and asked why. It turns out that not filling the glass to the point of overflow (and they do that with other drinks as well) is rude because it means that you are not offering the maximum capacity that the container can hold. Now, imagine holding the full, hot, handle-less, wet, dripping cup in your lap with your hands every time you want to drink a coffee. Yah, it’s a very particular experience!

DUMERSO WASHING STATION

Once again late at night (22h) we visited another washing station in full operation. When cherries need to be processed there is no rest, one cannot afford to let the sugars in the fruit start to ferment before the time and spoil the quality of the harvest.

As we saw at the Konga Sedie Station the night before, the cherries are weighed when they arrive at the mill and poured into a large funnel that transports them by gravity with the help of water to the pulper.

The pulper separates the seeds into the following categories:

GR 1: These are the seeds that sink first as they are the largest and have great promises inside that give them weight (they are prepared for export).

GR 2: They sink more slowly because they are smaller and weigh less

GR 3: “Floaters, unripe, brocade and defective coffees that do not weigh and float on the surface (unfortunately they are consumed locally).

Once pulped and separated, they go directly to their respective fermentation tanks.

GR 1: 36h – 48h fermentation + washing in channels + 10h – 12h soaking to remove any residual mucilage Once pulped and separated, they go directly to their respective fermentation tanks.

GR 2: undergoes a similar process to GR1 but sometimes with less soaking time.

GR 3: is not given much importance and can be left alone for 24 hours fermenting without any subsequent soaking.

The trip to Ethiopia has just begun, stay tuned for upcoming blog posts!

To be continued

Amesegenallo Ityop’ya

(Thank you very much, Ethiopia)