I’d been planning this trip to El Salvador since 2020, but when the pandemic reared its head I had to put it on hold, so I was delighted when I finally got to make it earlier this year.

Traveling to origin not only opens my senses, it connects me with my own role as a communicator, giving a voice to all the coffee farmers I know. I like to keep a journal on these trips, to describe the experiences and the people I’ve had the pleasure of meeting, as well as taking note of how the trip increases my knowledge and understanding of coffee.

Day One — The flight and not much more

The day ahead of me will be dull and exciting in equal parts, crossing the ocean that will bring me to my next adventure. I take a 9am flight from Barcelona to Madrid and a couple of hours later I’m boarding my flight to San Salvador, and meeting my partners in this adventure — Henry, Natasha and Brandon are roasters from the French coffee industry, and Caroline is the representative of Belco, the importer behind the organisation of this trip.

We arrive in San Salvador at 7pm with the familiar smell of a tropical climate awakening my senses, and I feel the jump in temperature. I’m tired but with all the newness I can’t help but feel excited.

Day Two — Saturday 11/2

7.30am start. We’re picked up by Jaime, who will be our driver for the whole week, and Rodrigo, the head of coffee sourcing for Belco in El Salvador. We’re headed to San Miguel to visit the La Alpina finca, a two-hour drive. Before setting off, we make a stop along the way at The Corner, a typical Salvadorian joint. Breakfast options are naturally savoury, and they include scrambled eggs, pancakes and papaya, lots of papaya, and pineapple. The fruit here has a sweetness that is so distinctive, it’s addictive.

With a full stomach, we head towards the finca. We arrive at the property, with the Chaparrastiqué volcano looming in the distance, and are greeted by Eli. He is responsible for all the different farms belonging to La Alpina and manages the agronomists of each farm. He’s joined by Armando, who looks after this property exclusively, overseeing global activity here – pickers, process, planting and production. Covering approximately 144 hectares and located at an altitude of 1,200 metres, here they grow Bourbon, Pacamara, Costa Rica and Pacas.

The volcano is very close by and I notice that the ground beneath me is very different from other farms — volcanic soil, which is sandy as it was formed from the stones of the adjacent volcanic activity. We walk through the plantation, stopping to look at a water tank where rainwater is collected and serves as a supply for the entire farm. Continuing with the walk, Eli tells me about a curious tactic of his to improve growth, what they call “agobio” or stress: they take the plant, bend it and tie it with a wire, which serves to stimulate new branches.

The porcess:

For washing, cherry is picked at the perfect point of ripeness and placed in two channels of water to process, separating by float. It is then pulped by friction, eliminating the mucilage by contact with water (called “cleaning”), and from there it is brought to patios to dry. I ask if they ferment in tanks with water and they explain that they don’t, due to lack of water. I think to myself that this cannot be a complete wash, that some mucilage must remain attached to the grain, however, every time I go to origin I realise that I have to put aside the systematic rulebook of the student and get to grips with the situation of each country.

For the naturals, they pick the ripe cherries and let them dry in the sun for two weeks on raised pallets. Then they are pulped and stored.

We have lunch at the finca and, later, after visiting the processes, we leave for the town of Alegría where we spend two nights. Alegría is a town with a great vibe and loads of life, with a central square with street food and music.

Day 3 — Sunday 12/2

No coffee, just cocoa.

A different kind of day awaits me today. Today the focus is not on coffee, but cocoa. We’re half an hour away from the cacao farm that we’re going to visit, run by the same owners as La Alpina. The finca is called La Catarina and Eli will again be our guide.

We’re in Catón de Tapesquío, located in the department of Usulatán. A 4-hectare piece of land at a lower altitude than the day before, this is where cocoa is grown. Unlike coffee, the trees are much taller and larger; and from them hang the cocoa pods. The pods are all different colours, green, brown, orange, white… we can tell by the colour which are ripe and which are not. There are two ways to tell if the cob is ripe: its colour, which is usually orange or yellow, or by knocking on the pods – if it breaks on impact, you know it’s ripe.

Five different varieties are grown here, and plants typically take two to three years to produce. They initially brought seeds from Honduras, from an Institute there that focuses solely on the study of cocoa, but they didn’t get the results they wanted. With the collaboration of Imperial College Selection (UK) they moved on to a selection of species from Trinidad and they now have a total of around 6,000 cocoa plants. They are planted three metres apart in rows, which is important for the pollination of the plant because some are incompatible with others. The plants are irrigated by drip and each plant consumes around 18 litres of water weekly.

Stand-out differences to coffee

– The cocoa plant produces all year round and the workforce is much smaller.

– The cocoa market is much more stable than the coffee market.

– Fine aroma is what they call quality cocoa. Similar to how we describe specialty coffee.

HIGHLIGHT:

I tried the cocoa bean mucilage and it was tremendous! The layer of mucilage is bigger than that of the coffee bean and has a really delicious taste of tropical fruit, melon and citric acidity.

Later, we had lunch in front of the Pacific Ocean, a completely new experience for me since I had never seen it, let alone swim in it.

At dinner that night we tried Pupusas: a typical dish here of tortillas filled with beans.

Day 4 — Monday 13/2

At last, I’m going to Los Pirineos.

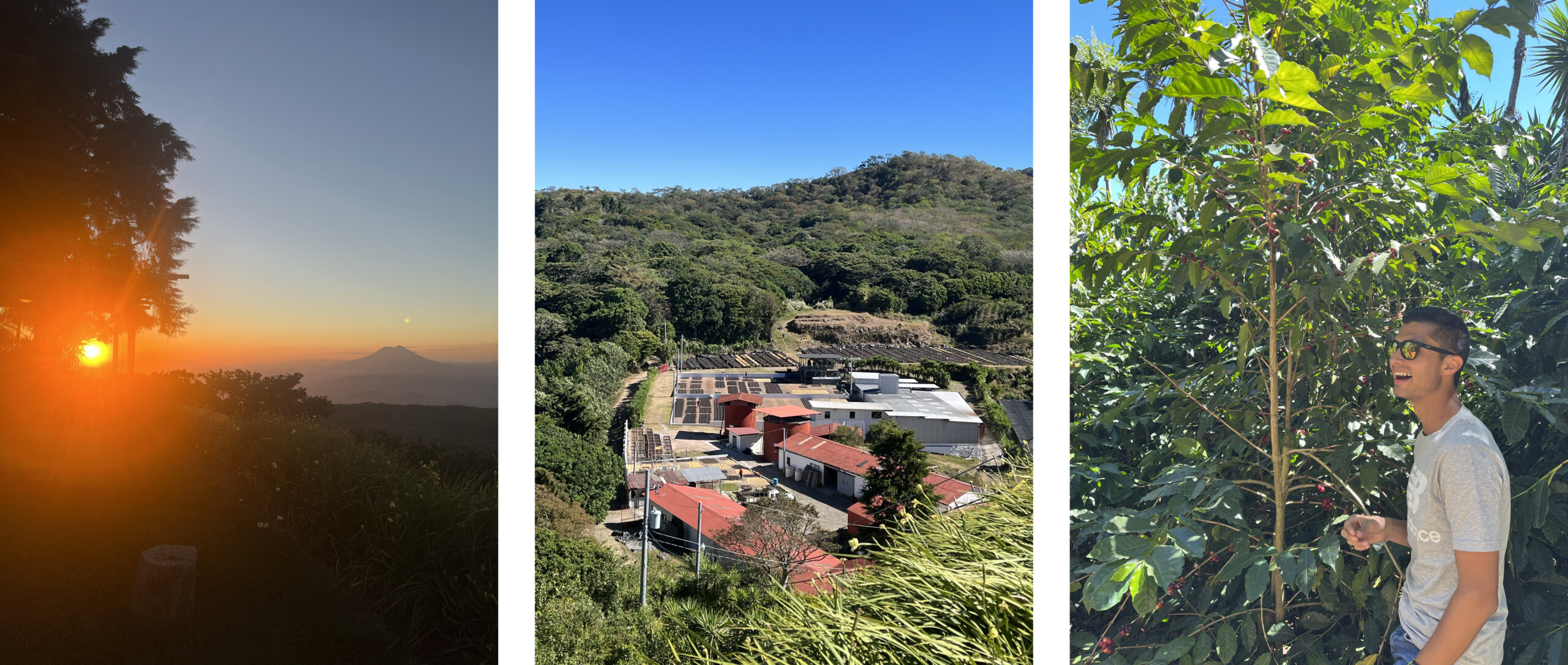

Today we’re going to visit one of the most famous fincas in El Salvador, Cup of Excellence winner many times over and owned by a very good friend of my whole family: Diego Baraona. We leave our hotel in the town of La Alegría and hit the road. It’s sandy and full of potholes, but the landscape opens up before us. Two red columns announce the beginning of the finca with the coffee trees already in sight. We continue up and up, knowing that spectacular views await us of this incredible mountainous landscape. As we ascend, I feel especially excited to be here. It feels like closing a very powerful circle of a parent-child relationship that Diego and I have had in common since our parents became close friends. I would have loved to have met his father Gilberto before he died, I know he was a man with an extraordinary love for coffee. Despite the sadness on the loss of his father, Diego is capable of transmitting that same limitless passion to me and that makes me happy

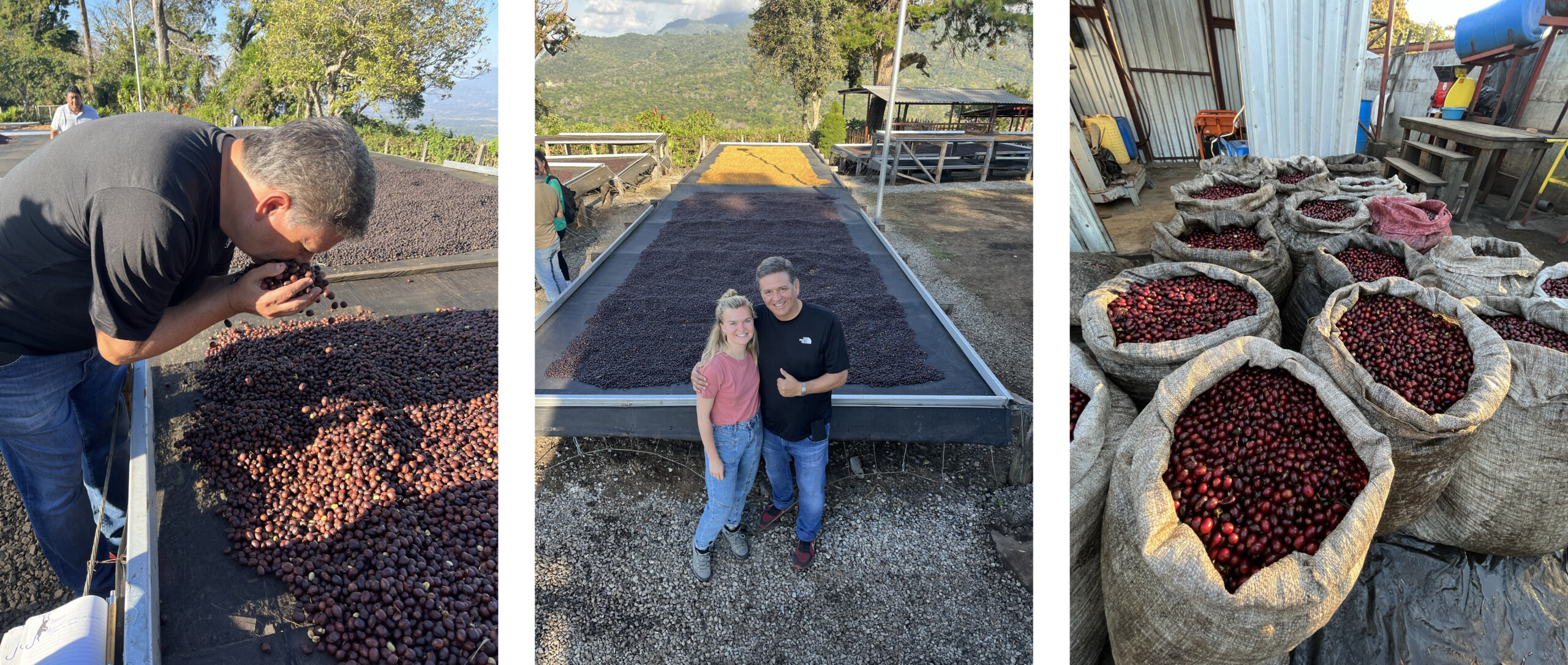

We’ll be sleeping at the top of the house, and from here you can see the volcano, the mountains and the whole process. The farm is 140 years old and Diego is the fifth generation of the family to manage it. They called it Los Pirineos after the mountains in my country – Diego’s great-grandparents’ parents were from Andorra. We are 1,600 miles above sea level and varieties such as Pacamara, Bourbon Elite, Pink Bourbon, Orange Bourbon, Geisha, Rume Sudan and SL28 are grown here. They put a huge amount of effort into nourishing the plants and giving them shade for better metabolisation. During the harvest season between 65 and 70 people work here.

On this finca, Diego produces around eight container’s worth of coffee, with each container fitting approx 200 sacks. He processes washed, honeys, naturals and anaerobic fermentations that are dried in elevated wooden pallets, with 17 of these just for honeys and naturals.

After checking out the drying beds, we head to the variety garden. Diego brings together a total of 80 different varietals in this garden, monitoring how each one reacts to the terroir in order to decide if it is worth producing it on the farm.

We continue towards the germination site and the nurseries. Diego plants 20,000 new coffee trees every year (about 3,000 per square). This is how he keeps the farm young, and every five years he sees the benefit of this annual planting.

We’re staying the night in this wonderful place, and soon after this last bit of the tour we head back to the house to sleep, since we’re planning a 5:30am wake-up call to see the sunrise.

Day 5 — Tuesday 14/2

After witnessing the beautiful Los Pirineos sunrise, we set off for San Salvador to visit the Belco office.

The Belco office is located in one of the city’s nerve centres and is equipped with a sample roaster and a cupping table for the batches that arrive from different farms. The work they do is crucial for getting the word out about new farms, introducing them to the market and helping coffee farmers. After the visit, we head for Apaneca to check out another pioneering finca in El Salvador: El Divisadero, owned by Mauricio Salaverria.

We arrive at the department of Ahuachapán, which is very close to the Guatemalan border. Mauricio comes looking for us and takes us to Villa Galicia, the nearest farm. The company is named after El Divisadero — the dry mill — and incorporates six farms in total: Himalaya, Villa Galicia, Cruz Gorda 1, Cruz Gorda 2, El Copo and El Divisadero, with each bearing different characteristics. For example, Cruz Gorda 1 delivers the lots with the largest volume, El Copo is the smallest and highest, while Villa Galicia is smaller and has more shade.

Grown here are varieties Anacafe14, Marsellesa, Pacamaras, Sl28, Pacas, Sachimor from Costa Rica and Lempira, which is native to Honduras. Mauricio explains that Bourbon and Pacas are less resistant to the elements and that is why he decided to plant more robust varieties, such as the Marseillaise. As he tells us all about the farm, he introduces his right-hand man Jesús Guerra, who describes how they process. Cherries are separated by float, placed on raised beds in piles for two days, then flattened and left them for about 23 days.

The Villa Galicia farm has a dimension of around twenty city blocks, with a wide variety of shade trees such as Pepet, La Inga, a guava and a medlar.

After our tour of the farm, we go to the apartment where Arnaud gets a barbecue going for us and I have some really delicious papaya. Over dinner I meet César – Belco’s cocoa export manager, Adriana – who will be taking us tomorrow to the El Manzano finca, and Christophe – owner of Terres du Café in Paris.

Day 6 — Wednesday 15/2

Today we’re going to visit El Manzano. For breakfast we make a stop at César’s hotel where they serve a wonderful Geisha filter coffee and María makes us some other-worldly banana pancakes.

We then set out on the road to El Manzano, where Adriana will be telling us about the different farms and projects of the Odyssey company.

Odyssey is a company that encompasses four farms run by Emilio López and José Roberto – these are La Cumbre, El Manzano, Tapantogusto, Las Isabelas and Las Piedras. We meet some key members of the team – logistics manager Isaura, Moises who runs the laboratory, and of course Adriana, who has been working with Emilio for five years.

What does Odyssey do? They produce, source, process and provide storage, with offices in the US and San Salvador, and for the last ten years have partnered with Belco for the European market. Their objective is to create a network of good conditions for workers, the environment and sustainability… a good example is the training they provide pickers with, to help them to improve their skills.

El Manzano is located in Chalchuapa, Santa Ana at about 1,300 metres above sea level. Founded in 1872, it spans a total of 70 hectares and they grow Yellow, Red and Orange Bourbon, Pacamara, SL34, Pacas, Geisha and Caturra varieties. They do both wet and dry processing, and produce a total of 25,000 sacks. They have raised pallets for drying, plus patios and mechanical dryers.

After telling us about the different farms, Adriana briefs us on the GROWING TOGETHER project. As you can imagine from the name, this is a sustainability program that works hand in hand with small producers, providing them with technical and agricultural knowledge. They do this through a series of seminars where producers are invited to come and learn about new technologies and ways of planting and processing. They also provide medical support, offering health checks and eye exams in schools, and free glasses for children.

When the presentation is over, a cupping of eight coffees awaits us in the outdoor patio and then we stop for lunch. Following that we have coffee, a little break in the sunshine before resuming our tour, walking to see the dry mill and other parts of the farm. Like Diego, here they try out different varieties in one part of the garden to see if they are conducive to the terroir, but the majority are Bourbon and Pacas.

Next, we walk to the roaster that is located in another building on the farm (the old church) where they roast for the local market under the name of Topeca. After checking it out, we head to the pulper and to the drying patios, where Enrique, who is in charge of the mill, is waiting for us.

PROCESS:

The cherries are first lowered by gravity into two piles: one for general coffee and the other for specialty. A hydraulic separator divides floats and leaves onto one side and the heavier cherries on the other. Natural coffee goes directly to the patios, and washed coffee is first pulped and then placed in two piles with mucilage for ten to twelve hours, later going through the “washing machine”, where the mucilage is removed. Once the wet milling is completed, grains are placed in drying patios for three days and then moved to mechanical dryers for 36 hours at 45 degrees Celsius.

At the El Manzano farm they also have a thresher.

Once the visit to this finca is over, we head towards another, La Cumbre, where we share a few beers and enjoy the views beside a magnificent fire. From there, we grab some Pupusas along the way (getting to like this typical dish from El Salvador) and go to the hotel run by César where his band are playing a concert.

Day 7 — Thursday 16/2

I had bid goodbye to the rest of group last night, as my travelling companions are headed to Guatemala and I’m staying on here. Today I’ll be with César and Christophe, visiting another cocoa farm.

As we drive, César tells me about the history of cocoa in the country. Izalco and Caluco are the departments where the most cocoa is produced. At the time of colonisation, cocoa was brought from El Salvador to Mexico, from there it was widely distributed and sold in Spain, in the French part of the Basque Country. However, it is important to note that cocoa is born where the Amazon begins and it was the Incas who brought cocoa to Central America. The Mayans and the Aztecs would later treat it as a healing drink, revered by the gods.

Regarding cocoa varieties, we can say that there are three main ones: Criollo, Trinitario and Forastero. I must mention that Trinitario is a hybrid of Criollo and Forastero, which presents complexity in the mouth in terms of flavour, and resistance in terms of plant resistance to combat climate change.

The farm:

We arrive at the farm, meet Jonás, the agronomist responsible for the plantation, and head straight into the cocoa trees. A crystal clear river runs nearby, providing water to dry the trees as the plant needs heat, light and a lot of water. It is harvested throughout the year, although the harvest peaks run from May to October.

For the cocoa fermentation process, beans are separated from the cob by removing the damaged beans. They are placed in a first wooden box where alcoholic fermentation takes place, and then spend five to eight days in another wooden box for acetic fermentation. The inside temperature of each box cannot exceed 48 degrees, which is why there is more than one box for the fermentation process. When the beans reach 75% fermentation, they are removed.

Afterwards, they are brought to the drying beds. A protective cover goes on for a few specific hours so that the beans do not dry out too quickly. When they reach 6% humidity, they are removed and Jonás carries out a balance test, choosing 25 broad beans and splitting them open. At least 18 have to be brown inside.

Finally, we try the cacao liquor, which is basically the bean ground into a paste. This determines how the cocoa tablets are to be made, let’s call it the master chocolatier’s way of tasting. From this, they decide how they are going to treat the cocoa and make the chocolate.

From here we go to El Salvador, where I stay one more day at Diego’s family’s house and then return home.

Until the next adventure!