Leyendo el nuevo libro de Maxwell Colonna-Dashwood Coffee Dictionary llegó en la página 218 a la descripción de lo que venimos llamando «Third Wave» y leo que fue acuñado por «el experto de la industria Trish Rothberg y ha sido ampliamente explorado por otros. El término es básicamente para USA pero las ideas detrás del concepto que describe una aproximación cambiante al café, pueden ser aplicadas a culturas alrededor del mundo.

La primera ola fue la comercialización del café, mayormente definida por un mercado masivo de café instantáneo.

La segunda ola fue la emergencia de las grandes cadenas de cafeterías que hoy copan las calles más importantes de las grandes ciudades, como Starbucks».

Me doy cuenta de lo incómodo que me siento con esta descripción como europeo, tostador y amante de la historia del café y me pregunto si todos estos nuevos baristas, microtostadores y propietarios de coffeeshops que surgen en Europa hoy y que se apuntan al concepto Third Wave conocen cuales son las dos olas anteriores o se autodenominan así porque queda bien, es moderno, les hace formar parte de una tribu y está escrito en inglés. Yo, por supuesto, no estoy en esta línea de pensamiento.

La cultura europea del café nada tiene que ver con «un mercado masificado de café instantáneo» excepto para los países anglosajones.

A mí me parece que el invento de la Sra. Melitta Benz o del Sr. Alfonso Bialletti cuyas cafeteras inundaron la inmensa mayoría de las casas europeas si son dignas de figurar en la historia del café como un cambio radical en la forma de preparar fácilmente la bebida contribuyendo decisivamente a incrementar el consumo de café en los hogares. En la restauración, sin duda, la fabricación de las máquinas espresso en cadena las lleva todos los rincones del mundo poniendo de moda tomar café en cualquier momento recién hecho.

Yo me siento heredero de la cultura europea del café ,que se puede ver y sentir, los bellísimos cafés de Trieste; en los cafés vieneses de Freud, Zwieg o Musil; del madrileño Café Gijón de Ramón y Cajal, Garcia Lorca o Cela, o el barcelonés Els Quatre Gats de Ramon Casas, Picasso o Puig i Cadafalch; de los cafés de Paris donde se urdió la Revolución Francesa o en aquellos donde se reunían Sartre, De Beauvoir, Picasso, Gide y tantos y tantos otros cafés a lo largo y ancho de Europa donde se hacía política, arte y liberalismo. Reconociendo la contribución de algunas grandes cadenas, yo me siento más afín culturalmente a lo anterior.

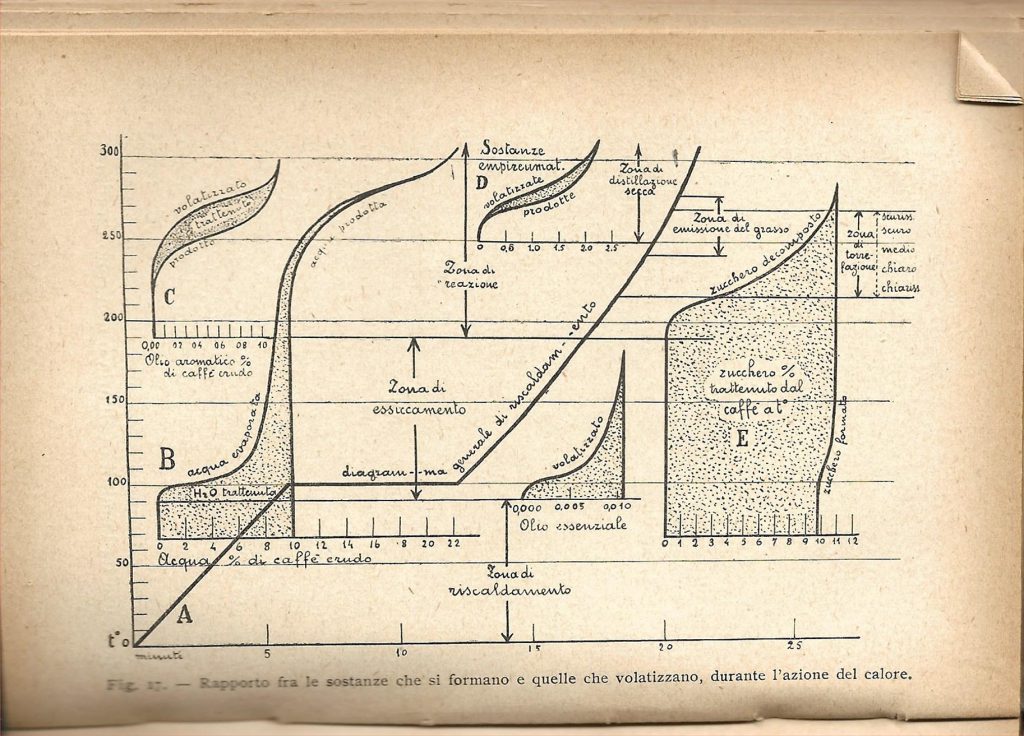

Para poder abastecer a todos estos lugares había importadores en Hamburgo, Bremen, Trieste, Barcelona, Le Havre… Y sí, viajaban y traían cafés que tenían también denominaciones de origen y escribían libros y creaban centros de estudio. ¿Conocéis a René Coste? En los años veinte viajó por África donde contrajo la malaria y escribió un increíble libro en tres volúmenes sobre el café que publicó a finales de los 50, fue Director General del Instituto Francés del Café y del Cacao embrión del CIRAD. ¿Philippe Jobin? viajó por todo el mundo y escribió Les Cafés Produits dans le Monde. El italiano Leonida Valerio del que no he podido encontrar biografía con su Café e Derivatti publicado en 1927, química, curvas de tueste, máquinas de espresso. También todos somos sus herederos y no merecen ser olvidados, antes al contrario.

Caffè e Derivati 1927

Caffè e Derivati 1927

Ya en 1927 se estudia la relación entre las sustancias que se forman y las que se volatilizan durante la acción del calor en el tueste.

En definitiva, explicar la historia mundial del café con estas tres «waves» seria como explicar la historia de la cocina por lo que se ha comido y cocinado en USA o Inglaterra.

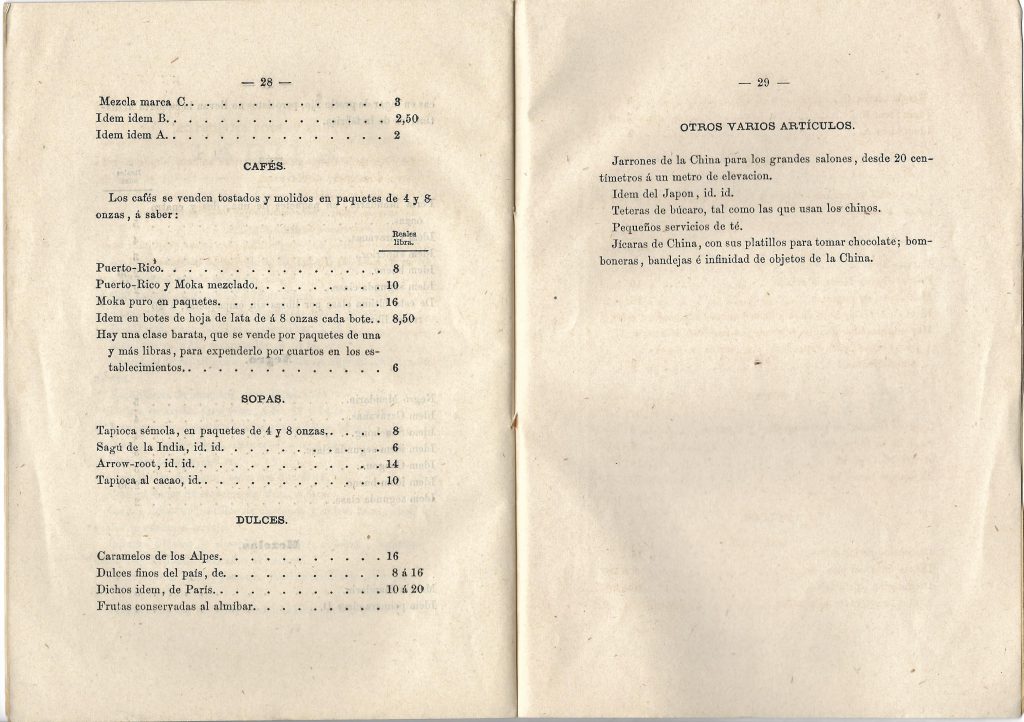

Matías Lopez y Lopez 1870

Cafés en venta en Madrid en 1870, pág 28 ya en 1870 se vendía café de origen en Madrid

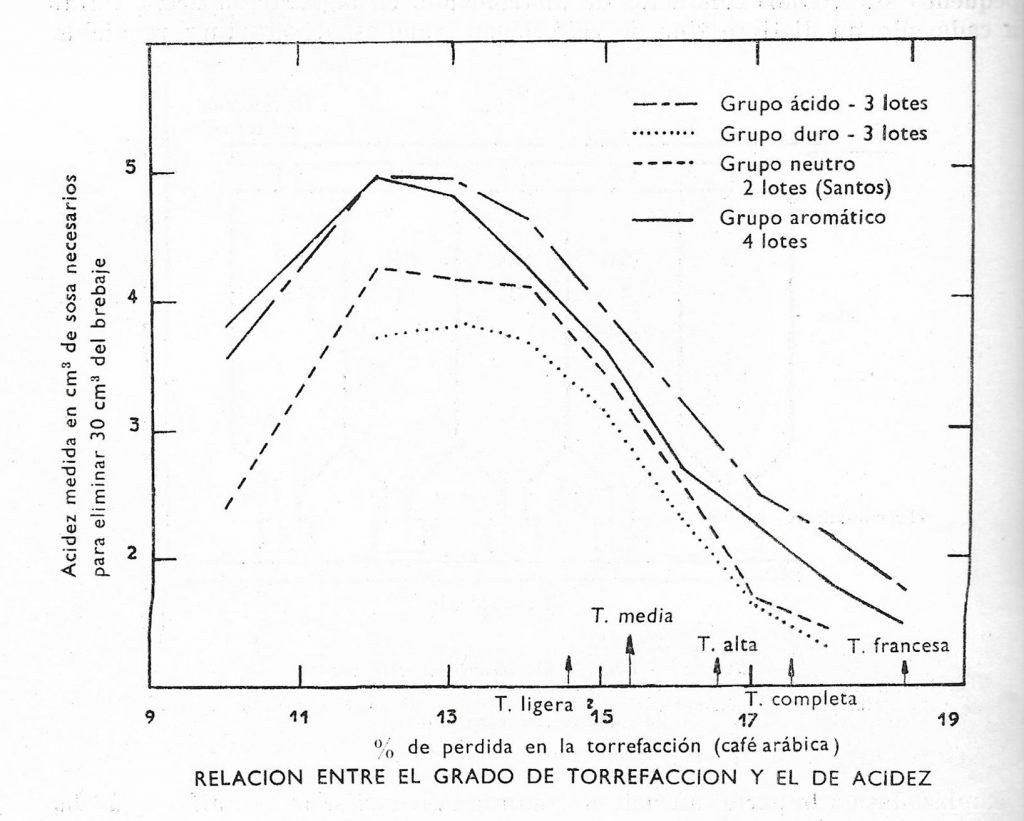

Cafetos y Cafés 1924

Torrefacción y acidez, ya en 1924 se evaluaba la relación entre el grado de tueste y la acidez.

Referencia de los libros escaneados:

1 “Breve Narración y Apuntes acerca de la Utilidad y Preparación del Café”

autor: D. Matías Lopez y Lopez, 1ª edición 1870, Madrid.

(Premiado en las Exposiciones de Londres, Peris, Bayona, Oporto, Zaragoza, Madrid y otras varias nacionales y extranjeras)

2 “Caffè e Derivati” Manual Hoepli. Industrie – Comercio – Usi – Sfruttamenti Nuovi e Razionali.

autor: Leonida Valerio, 1927, Milano.

3 “Cafetos y Cafés en el Mundo” Sindicato Nacional de la Alimentación, Grupo de Torrefactores de Café.

Traducido de la Obra de D. René Coste, editado por Larose-Paris 1964.

Tomo segundo, Volumen 1.